“Before the war on drugs in the 1970s, there was a range of promising research into therapeutic psychedelics”

Adrià Voltà

In the early 1950s, Albert Einstein, Carl Jung, Graham Greene and many other leading figures from science, philosophy, culture and politics were featured in plans for a gathering – dubbed “Outsight” – where they would take powerful psychedelics. Things took a different turn, but I am fascinated by what might have been.

I have been investigating psychedelics for The Trip, a new BBC Radio 4 series. I had previously written about the unsettling, vivid hallucinations I had while in a coma in hospital with covid-19. This was something I wasn’t keen to repeat, but I wanted to understand why people were deliberately seeking out psychedelic experiences, visiting places where the laws are different or taking risks (legal and otherwise) at home to seek healing or fulfil other unmet needs.

It was never a given that the international community would come to broadly prohibit psychedelics. The enquiring minds of scientists from Humphry Davy, who experimented with the effects of nitrous oxide in 1799, to Humphry Osmond, who coined the word psychedelic in the 1950s, saw that chemically induced altered states required rigorous, thoughtful cross-disciplinary study.

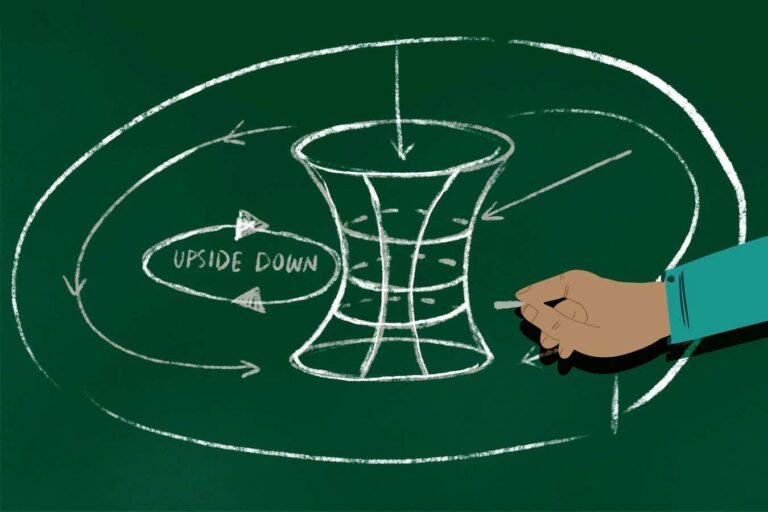

Before the US-led war on drugs began in the 1970s, there was a range of promising research into the therapeutic potential of psychedelics. There had also been a long history of their use by Indigenous cultures in sacred and ritual contexts. But rather than science being allowed to follow its course, everything was driven underground. As a result, it feels to so many of us that these substances, derived from fungi and plants or synthesised in labs, are somehow other. It is this otherness that astonished me in its ability to linger.

Today, psychedelic research is picking up steam once again around the world, looking at whether such drugs can help with depression, addiction, PTSD, eating disorders, dementia and intergenerational trauma. There is work on their possible use to extend the window for recovery after a stroke, giving more time for rehabilitation, and even as a way to understand consciousness.

As we spoke to researchers quietly and objectively testing substances such as psilocybin and DMT in clinical settings, it all felt like a world away from the psychedelic narratives of popular culture. These molecules have profound, lasting effects upon the mind and our perceptions of reality. It is hard to understate how strange it now seems that we chose to simply cut off broad avenues of inquiry, and refused to allow our best minds to see where they might really lead.

Conversations with today’s researchers are as interesting as it gets, but for me I can’t shake off the “what if?”. With a global mental health crisis, governments and health systems are desperate for new treatment options. Public funding is being cut and is under threat in many territories. At the same time, big business, with its profit motive, is taking a keen interest, with implications for the accessibility of new treatments. Things are changing, fast.

Once you attempt a clear-eyed look at the history of humanity’s relationship with psychedelic molecules, the story is one of a giant, self-inflicted wound. Ultimately, the funding for Outsight didn’t come through and a very different era began. The war on drugs all but closed down research into a whole class of substances for decades, with ramifications lasting to this day.

The story of these substances is a warning. Politics can’t be allowed to impede scientific discovery. Looking around the world today, I see an urgency – I would say a moral imperative – to protect and nurture the conditions in which science can get on with the job. The stakes are too high not to.