Even in the face of vast fields of flowers, local bumblebees may face the sting of competition when people bring their honeybees to the floral feast.

When beekeepers truck their hives to a mass-blossoming event in upland Ireland to forage for nectar, local wild bees end up smaller than usual and focus on foraging for their young, researchers report December 10 in Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. This could mean they’ve been bumped over by the human-raised bees, potentially stressing an important pollinator.

The late-summer bloom of heather in the Wicklow Mountains of Ireland coats the range in lovely purple flowers. Beekeepers traditionally move hives to the heathlands for the event. Like buses full of tourists in Times Square, the farmers’ honeybees (Apis mellifera) descend on the local nectar supplies.

The local wild bumblebees tend to live in smaller, more seasonal colonies than honeybees, which live year-round. During the heather bloom, bumbling workers gather nectar to feed themselves and pollen to feed their young, a few of which will grow into queens that will overwinter, while the rest of the colony dies. The heather is key to this strategy. “So suddenly, having lots of competitors arriving on the back of a lorry is not ideal,” says Dave Goulson, an entomologist at the University of Sussex in England who was not involved in the study.

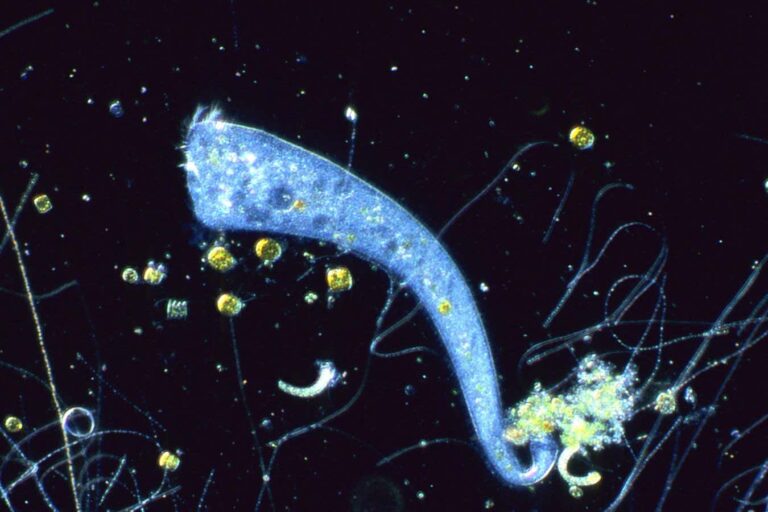

Dara Stanley, an ecologist at University College Dublin, and her colleagues wondered how the temporary bee boom might affect local bumblebees. They strode through fields of blooming heather, gently catching and measuring members of six species of local bumblebees (such as the white-tailed bumblebee, Bombus lucorum, and the small heath bumblebee, Bombus jonellus) and the honeybees from nearby hives.

The honeybee crowds did not affect the number of bumblebees nearby. But bumblebees the scientists measured in honeybee-heavy areas were smaller than those elsewhere. Larger bumblebees could be going to areas with fewer honeybees for better nectar opportunities, leaving small bees to forage in crowded areas, Stanley says. Or the bumblebee colonies could be having trouble taking in enough food, sending out more workers to forage — resulting in smaller bumblebees doing the grocery run.

The scientists also followed local bees to observe their behavior and saw that smaller bumblebees were more likely to be foraging for pollen rather than nectar. Pollen is nutrition for bee young, Stanley says, so “when a colony is under stress, it might prioritize reproduction or pollen collection for larva.”

It’s a subtle change in behavior, but the information could help guide beekeepers toward more ecological hive placement, Goulson says. While moving bees to flowers might be fine in more agricultural areas, findings like this and others suggest that honeybees shouldn’t be buzzing around nature reserves in the heathlands. “We do know that wild pollinators have been in decline for quite some time,” he says. “Anything that contributes to their woes is something we should pay attention to.”

Source link