A telltale hint was on the bee’s knees.

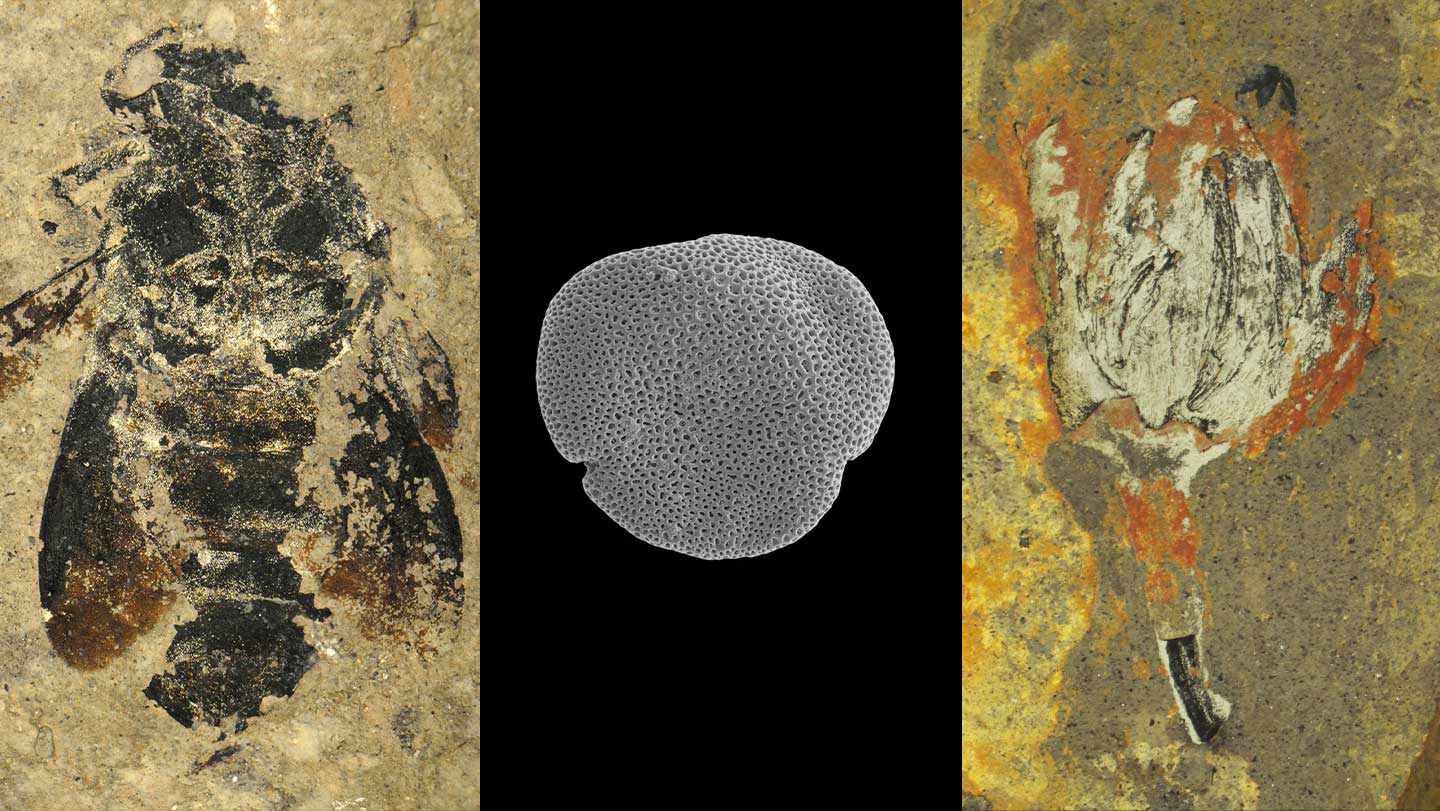

An analysis of 127 fossil flowers, flower buds and bees from central Germany revealed pollen particles that precisely matched ancient flowers to their pollinators. The fossils date to around 24 million years ago. While evidence of earlier pollen-covered insects exists, this is the oldest example of a direct pollination relationship observed between any two species, researchers report September 22 in New Phytologist.

“The mere presence of pollen adhered to the body of a fossil bee only confirms the insect made floral visits,” says Constanza Peña-Kairath, a specialist in ancient insect pollination formerly at the University of Barcelona who was not involved in the study. The new research provides “a crucial and exceptionally well-preserved piece of evidence” of an unambiguous relationship between pollinator and the pollinated, she says.

Researchers collected the fossils from an ancient crater lake in Enspel, which lies about midway between Düsseldorf and Frankfurt. Millions of years ago, vegetation lined the lake and bees thrived along the shoreline. Occasionally, bees and flowers would fall into the lake and get covered by sediments that would later fossilize their remains.

“Insects fall into water bodies and drown all the time,” says Christian Geier, a paleobotanist at the University of Vienna. “In the case of the fossilized bumblebees, they escaped being eaten by fish and ended up sinking down to the bottom of the lake.”

Geier and his colleagues identified a new species of linden tree flower, Tilia magnasepala, and two new species of bumblebee, Bombus messegus and B. palaeocrater. These are the oldest known bumblebee fossils in Europe, Geier says.

Both the flowers and bees were covered in pollen, which allowed the researchers to try and match the fossils like pieces of a puzzle.

Geier and his colleagues extracted pollen particles from several of the fossils and used a scanning electron microscope to peer deep into the structure of the pollen. The pollen in the flowers matched the pollen on both new species of bees. Additionally, the bees had pollen on the undersides of their body, including their legs, mouthparts and abdomens, indicating they collected the pollen when they landed on the cupped-shaped linden flowers.

Evidence of insects carrying pollen of nonflowering plants goes back at least 280 million years, long before an evolutionary burst of flowering plants around 130 million years ago. The subsequent widespread success of flowering plants — they now make up around 90 percent of modern plants — is in part due to their pollinators, prior research has suggested.

Today, linden trees still depend on bumblebees for pollination, making this the longest known “direct proof for a bee-flower interaction that is still ongoing in Europe,” says Friðgeir Grímsson, a paleobotanist also at the University of Vienna. Being able to trace a long-standing relationship between a plant and its pollinator back 24 million years “is what makes this so special.”

Source link