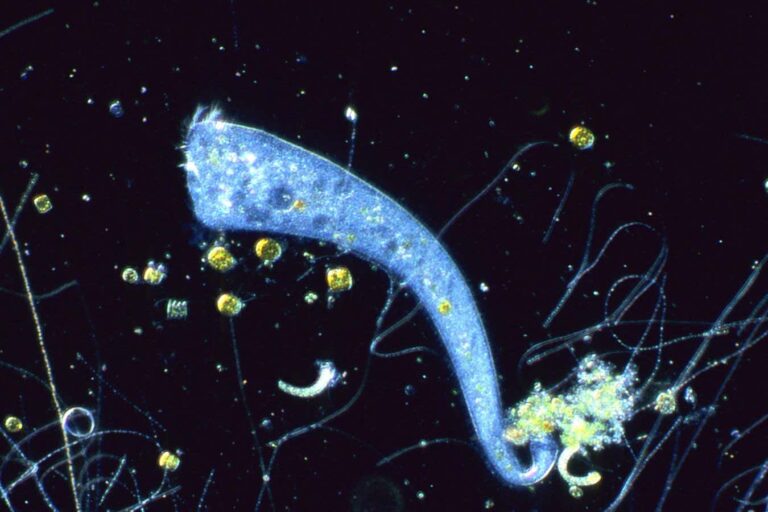

DGDImages / Alamy Stock Photo

I was wondering, as I began working on this story, whether to eat my subject as part of the research. I imagined a bold opening: “This is the longest-lived animal in the world – and it tastes great.”

Since the animal in question is a species of clam, I visualised a spaghetti alle vongole with plenty of garlic. But setting aside the ethical considerations of killing and eating a fellow animal, and the ecological damage we are doing in over-exploiting the ocean, I realised there is another consideration. This special animal – the ocean quahog – can live for at least 500 years. Killing it just seems wrong. So, no, I won’t eat this mollusc. As such, let me amend my introduction: this is the longest-lived animal in the world – and my mission is to discover its secret.

You can be forgiven if you haven’t heard of the ocean quahog, also known as the Icelandic cyprine: it isn’t the sort of animal that gets much TV time. It is a large bivalve mollusc that lives buried in the sand on both coasts of the Atlantic, from the southern warmth of Florida and Cadiz in Spain, to the colder waters of Quebec in Canada and Norway. If you have had clam chowder in the US, you will have almost certainly eaten it. Its shell is fine-lined like the rings of a tree trunk, and like tree rings, you can count these lines to tell its age.

The oldest known specimen was called Hafrún by researchers, an Icelandic name that means “mystery of the ocean”. Hafrún was born in 1499 and lived as its ancestors had done for generations, quietly on a modest diet gathered off the coast of Iceland. In that sense, its life was unremarkable, but for the fact that it went on and on – and on. It ended, in fact, only in 2006, when it was dredged from the sea by a team from the University of Exeter, UK. Sclerochronologist Paul Butler was the researcher tasked with ageing it. Sclerochronology involves analysing bivalve shells to construct timelines for their surrounding environments.

“Its age was initially published as just over 400 years, but closer reading of the growth lines and comparison with other shells showed it was in fact 507 years old,” he tells me. It is likely there are even older ones still out there, especially in the cold waters around Iceland, where they seem to grow more slowly and live even longer. Is there an upper limit to their age? “It’s hard to believe they live a lot longer,” says Butler, “although we did once get the ages of a few individuals analysed by a mathematician who said in principle they could live forever.” Well, that’s mathematicians for you.

The key to the longevity of the quahog appears to be in its mitochondria – the structures in our cells that use food to provide us with energy. By “us”, I mean us eukaryotes – all complex organisms, from yew trees and mealworms to jellyfish and rabbits.

“Having robust mitochondria, which Arctica islandica has, is paramount for healthy ageing in a wide variety of model species,” says Enrique Rodriguez, who researches mitochondria at University College London.

Quahog mitochondria are, quite literally, tougher. They have a membrane more resistant to damage than those in other species. The membrane of a mitochondrion is packed with protein machinery that processes electrons and protons and generates ATP, the universal molecule of energy used in cells. In quahogs, this machinery is bigger and more bundled together, which makes it more robust. “The proteins are higher-molecular-weight, more complex structures,” says Rodriguez. “They are more joined together.”

Thanks to this machinery, quahogs experience less damage to their mitochondria. This is partly because they are more careful at marshalling the billions of protons and electrons criss-crossing these membranes every second. When electrons leak, they produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as hydrogen peroxide, which cause damage. Rodriguez likens it to cars in a queue of traffic. In normal mitochondria, the red light at the head of the queue causes cars to back up, their exhaust spewing out and damaging the environment. In quahog mitochondria, however, the traffic light – in this case, a protein complex – is far more efficient at moving traffic, and less exhaust billows out of the cars.

But it isn’t just the robust membrane that helps a quahog have a healthy lifespan. It is also because quahogs mop up the ROS that do leak out. To use Rodriguez’s analogy, this would be like cleaning up car exhaust fumes.

A woman hunts for quahogs on the shoreline of Massachusetts

The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Rodriguez compared the antioxidant capacity of the quahog with a range of shorter-lived related species and found it has three to 14 times the ability to mop up ROS. All this adds support for what is known as the mitochondrial oxidative stress theory of ageing (MOSTA). This too seems to be behind the exceptional lifespan of the naked mole rat, which can live for 40 years, more than six times longer than other rodents of the same size.

Pierre Blier, a researcher in animal metabolism and aquaculture genetics at the University of Quebec, keeps quahogs in tanks in his lab in order to study the mechanism of their longevity. He confirms that ocean quahogs have a higher capacity to buffer oxidants. “Arctica islandica has mitochondria that are much more robust and able to resist ROS,” he says, supporting the MOSTA theory.

That begins to answer the question of how these animals live so long – but what about the why? In other words, what has been the selection pressure that has led to the evolution of such robust mitochondria?

A clue comes from the low levels of oxygen in the clam’s environment. “Arctica can stay with the shell closed without using their gills to capture oxygen for about a week,” says Rodriguez. Their mitochondria have had to evolve ways to survive for long periods with low or even no oxygen – known as anoxia – then be robust enough to cope with a sudden influx of oxygen and buffer the sudden increase in oxidative stress that results. This is also similar to naked mole rats. “Naked mole rats live in burrows with very low oxygen levels,” says Rodriguez. “We see similar patterns in the way their mitochondria are robust and geared towards resisting anoxia and reoxygenation stress and living a long lifespan.” So it is perhaps the case, he says, that selection for anoxia has delivered long lifespans almost as a side effect.

“

My advice to live longer is to do exercise, eat well and take cold showers

“

The big question, of course, is whether we can toughen up our own mitochondria. In 2005, a team at the University of California, Irvine, made transgenic mice that produced more of the “mop up” antioxidant enzyme catalase in their mitochondria, and this increased mouse lifespan by about five months – a significant amount when normal lifespan is two years. Although it is now possible to gene-edit human mitochondria, we are far from understanding how to safely increase lifespan, so we need another way.

We know that exercising improves the way our mitochondria perform. We also know that the Tibetan Sherpa people, who live at high altitudes, have different mitochondria from lowlanders. A 2017 study looked at native lowlanders and Sherpas ascending to Everest Base Camp at around 5300 metres above sea level. Sherpas were able to use oxygen better and had greater protection against oxidative stress because their mitochondria were more robust – and this had a genetic basis.

Blier insists that A. islandica really does have something to tell us about longevity. “My advice to live longer is to take care of your mitochondria: do exercise, eat well and take cold showers… Cold showers seem to induce quality control mechanisms of mitochondria.”

Well, if it works for quahogs…

Topics: