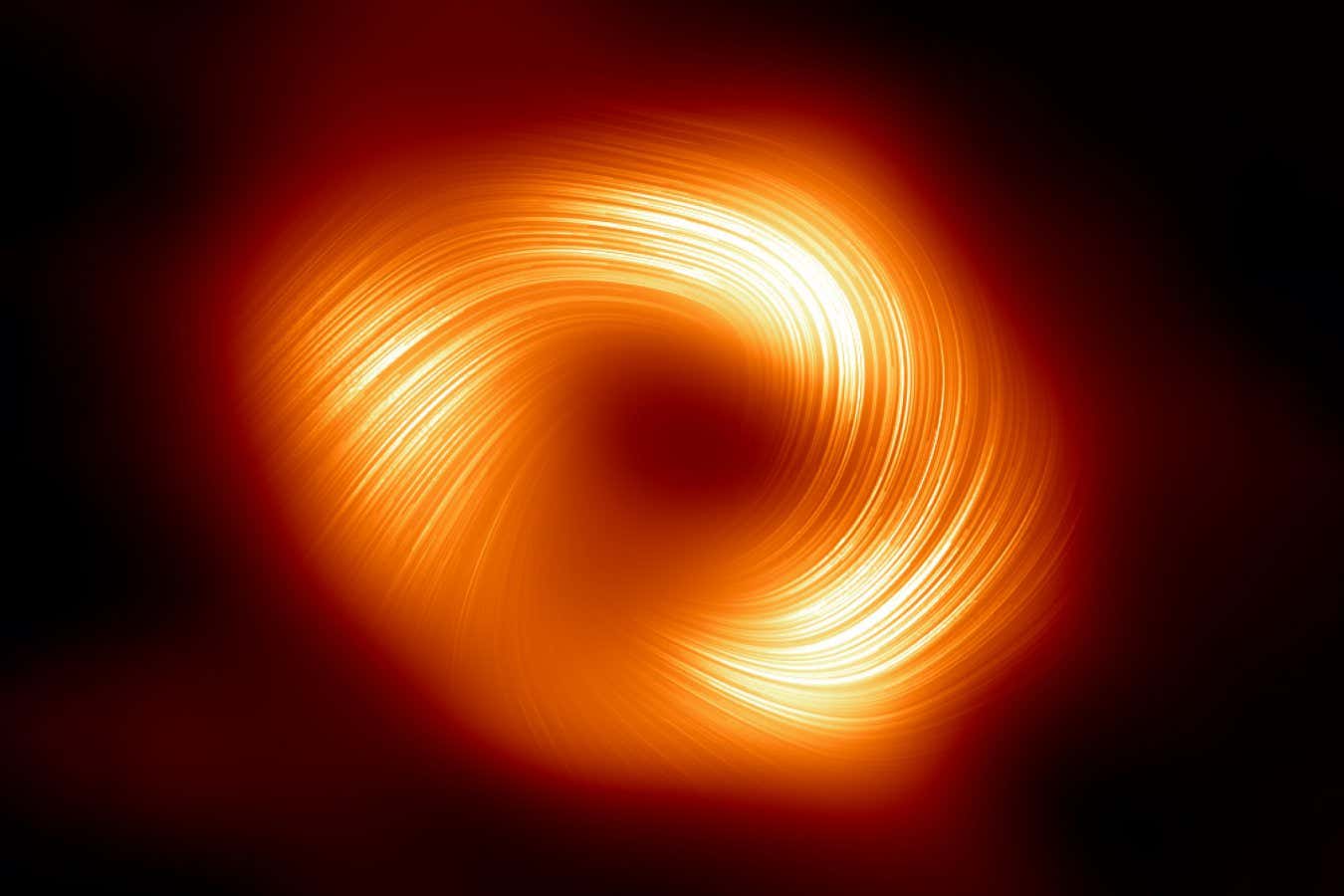

An image of the supermassive black hole Sagittarius A* in polarised light, captured by the Event Horizon Telescope

EHT Collaboration

At the centre of our galaxy lies a supermassive black hole called Sagittarius A* – but one group of researchers is suggesting it may not be a black hole at all. The team says that it, and other black holes around its size, may actually be clumps of dark matter.

Dark matter, so named because it doesn’t seem to interact with light or regular matter in any way except gravitationally, makes up about 85 per cent of the total matter in the universe, but we know very little about it. What we do know, because of the way galaxies rotate, is that most galaxies are embedded in a halo of the stuff. “We know it has to be at the outskirts of galaxies, but we don’t know what happens at the very centre,” says Valentina Crespi at the National University of La Plata (UNLP) in Argentina.

Crespi and her colleagues built a model of a galactic core made of dark matter in the form of extremely light particles called fermions. They found that fermionic dark matter could form a clump so massive and dense that, from afar, it could look almost exactly like a supermassive black hole.

“From Earth, you would see something very similar to what you would see in the black hole scenario – but if we went in a ship towards the centre, we could go through with no problem,” says Carlos Argüelles at UNLP, who was part of the research group. “You will not die by being eaten by the black hole; you will go through peacefully.”

Of course, we don’t have the capability to actually send a ship through the centre of the galaxy, so the team’s model is based largely on the orbits of stars and small clouds of gas close to Sagittarius A*. It also matches measurements of the rotation of the entire galaxy, as well as the image of Sagittarius A* released by the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) in 2022. The image shows a glowing ring of superheated matter around the black hole, which could also be caused by the gravitational pull of a dark matter core.

But just because the idea that Sagittarius A* is made of dark matter matches up with observations, that doesn’t mean it is true. “Based on the fact that it is a simpler answer that fits the evidence, I personally believe that the celestial body at the center of our galaxy is very likely a black hole,” says Gaston Giribet at New York University. “However… all possibilities must be analysed, and this is certainly an interesting one.”

One potential issue is that while a dark matter core matches the orbits of objects several light hours away from the edge of the black hole, known as the event horizon, it is unclear whether or not the model works for observations “at the very doorstep of the event horizon”, says Shep Doeleman at Harvard University, who is the founding director of the EHT project. In particular, the spiral pattern of the magnetic fields in that area seems consistent with a black hole, he says.

Another problem is that fermionic dark matter couldn’t form a clump bigger than about 10 million times the mass of the sun. In the abstract, this might seem like a positive: fermionic dark matter clumps could get about that massive and then collapse into black holes, which could explain the enduring mystery of how supermassive black holes grew so big. But the EHT image of a much larger supermassive black hole called M87* looks nearly identical to Sagittarius A*, even though M87* is about 6.5 billion solar masses, which could make the idea harder to accept.

The researchers concede that a dark matter core isn’t more likely than a black hole, and indeed it may be less likely. “Nowadays, with the instruments available, it is not yet possible to 100 per cent discriminate if it’s indeed dark matter or not,” says Crespi. To do that, we would need images at such high resolutions that even the next generation of the EHT will almost certainly get nowhere close, says Argüelles – it will be decades before we can say for sure, if not longer.

If Sagittarius A* is dark matter, though, that will be hugely important. Fermionic dark matter isn’t predicted by the current standard model of cosmology, which favours heavier, slower-moving particles as dark matter candidates, so a core of it relatively nearby would shake up our understanding of not just black holes, but the whole universe.

Spend a weekend with some of the brightest minds in science, as you explore the mysteries of the universe in an exciting programme that includes an excursion to see the iconic Lovell Telescope. Topics:

Mysteries of the universe: Cheshire, England