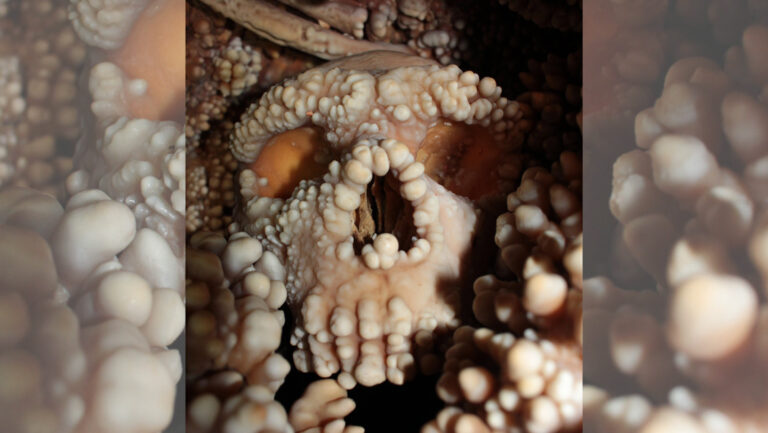

This image seems to show a wrench on Mars, but it is just an ordinary rock

Brian Cory Dobbs Productions

Blue Planet Red

Directed by Brian Cory Dobbs, Streaming on Amazon Prime Video

Blue Planets Red purports to be a documentary about Mars. The world presented by director Brian Cory Dobbs isn’t the one you and I might recognise, but it certainly has some appeal: it was home to an advanced civilisation of pyramid builders, who either couldn’t save their world from destruction or laid it to waste in an orgiastic nuclear conflict.

Dobbs delivers his arguments for advanced Martian life straight to camera, with many a raised eyebrow and artful pause. I quite liked him. But I wasn’t in the least surprised, after watching his film, to learn that his showreel partly consists of woo-woo (by which I mean questionable videos about mobile phones, electromagnetic fields and cancer).

Intentionally or not, though, Blue Planet Red is a historical document: the last hurrah of a generation of researchers and enthusiasts who came to maturity under the shadow of a 2-kilometre mesa, a type of geological feature, in the Martian region of Cydonia. Here, in 1976, where the southern highlands of Mars and its northern plains meet, NASA’s Viking orbiters snapped blurry images of what looked like a gigantic human visage: the so-called Face on Mars.

Let’s not spend too much time here debunking what has already been debunked, so often and so convincingly, elsewhere. Improve the image resolution and the face disappears. Rocks that look like tools and bones are just that: rocks. And the presence of xenon-129 in the Martian atmosphere implies ancient nuclear conflict only if you ignore the well-understood process by which a now-extinct isotope, iodine-129, would have decayed to xenon-129 in Mars’s rapidly cooling lithosphere.

“

The Viking orbiters’ ambiguous data was the perfect growth medium for fantastical ideas

“

Yet there is something poignant in capturing the idées fixes of this generation of researchers. Those who feature in the film include Richard Brice Hoover, who headed astrobiology research at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama until his retirement in 2011 and helped demonstrate the existence of extremophile life on Earth. He is convinced he has found microfossils in Martian meteorites. Despite his enthusiasm, Hoover never gets around to explaining in this film why each fossil is lying on the top of the rock sample, instead of being embedded within it.

Fellow contributor John Brandenburg is a pretty well-regarded plasma scientist, if you can get him off the subject of Martian nuclear war. And then there is Mark Carlotto, who has spent 40 years seeing civilisational remains on Mars where everyone else sees rocks. Drag him down to Earth and he is a capable archaeologist.

After the final Apollo moon landing in 1972, the initial excitement of the space race began to wane. The images the Viking orbiters sent back promised the next great discovery. Their blurry amalgams of groundbreaking-yet-ambiguous data were the perfect growth medium for fantastical ideas, especially in the US, where the Vietnam war and the Watergate scandal encouraged scepticism and paranoia.

Dobbs’s flashy retelling of tall Martian tales thinks it is about events 3.7 billion years ago, when a wet, warm planet turned into a dust bowl. For me, it is much more about what happened to a band of enthusiasts, glued to monitors and magazines in the 1970s. Let’s lay our scorn aside for a moment and look this generation in the eye. Fond hopes won’t trip up fine minds quite like this again.

Simon also recommends…

Mapping Mars

Oliver Morton

This exploration of Martian terrain describes how the human eye, aided by optical technology, brought our neighbour into focus.

The Mars Project (1953)

Wernher von Braun

The US-German (and Nazi) rocket scientist drew inspiration from Antarctic expeditions in this first, foundational technical specification for a human mission to Mars

Simon Ings is a novelist and science writer. Follow him on X @simonings

Topics: