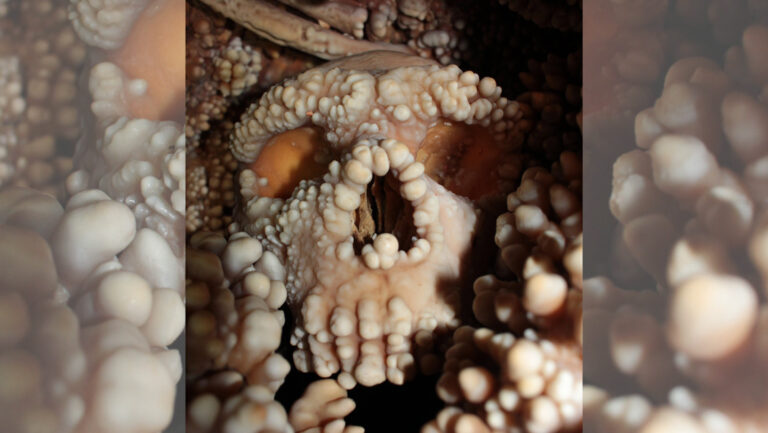

A solar future for this Sichuan pepper field in Bijie, China

STR/AFP via Getty Images

Here Comes the Sun

(Bill McKibben W. W. Norton, UK, 16 September; US, 19 August)

The sun is rising on solar power. According to Ember, an energy think tank, solar energy has been the world’s fastest growing source of electricity for the past 20 years, and it is accelerating.

In 2022, solar power capacity surpassed 1 terawatt for the first time. Just two years later, it had doubled, generating 7 per cent of the world’s electricity. When you include wind turbines (which capture the sun’s energy via a different mechanism), the sun generated 15 per cent of Earth’s electricity last year.

This solar energy boom isn’t due to countries suddenly getting serious about their climate commitments. In fact, according to another Ember report, most renewable energy targets still lag far behind the tripling that is needed this decade to stay on track for net-zero emissions.

The real reason solar power is taking off is because it has become the cheapest way of generating electricity almost everywhere.

In Here Comes the Sun: A last chance for the climate and a fresh chance for civilization, long-time climate activist and environmentalist Bill McKibben makes the case that this shift leaves the world “on the edge of one of those rare and enormous transformations in human history” where we transition from one dominant energy source, fossil fuels, to another, the sun. “We are on the verge of turning to the heavens for energy instead of to hell,” writes McKibben.

What follows is a stirring and closely argued account of how cheap solar energy now offers us a chance of not only tackling climate change on time, but of remaking our economies and our relationship to the natural world.

This is hardly the first book to argue for a rapid transition to renewable energy. But it is visionary in the way it goes beyond the technical and economic dimensions of the energy transition to explore what a sun-powered society might really look like.

An energy transition led by solar power might be inevitable, but it may not happen fast enough

“All of a sudden this entirely necessary conversion is also the greatest bargain of all time, one that could upend our conventional economics of scarcity and replace it with something we don’t yet fully understand,” he writes.

That this sunny optimism comes from McKibben, whose first book was entitled The End of Nature and who was among the first to raise the alarm about climate change, makes it much more powerful.

Instead of detailing the damage caused by climate change and how it could all get worse, he emphasises the benefits that could come from more solar power, such as lower and more stable energy prices and less dependence on petrostates.

On a spiritual level, he hints at how this shift could restore our sense of awe for the sun and its power.

McKibben is also alive to sceptics of renewable energy and offers balanced answers on how to address trade-offs of the energy transition, such as rising demand for minerals and land, and lost jobs in the fossil fuel industry. These are supported not only by numbers, but an eclectic suite of anecdotes from the early days of the energy transition around the world. I was delighted to learn, for instance, that the Kentucky Coal Mining Museum has switched to solar power to save energy costs.

However, there are plenty of reasons to doubt that all of these sun-powered dreams will come to pass as quickly as McKibben suggests they could. Remember, most of the extraordinary expansion of solar energy is happening in China. There is no guarantee that countries lacking China’s unique combination of manufacturing prowess, central planning and authoritarian politics can match that blistering pace. It might not even be sustainable there.

In the US, solar power has seen record growth for several years, but now it faces the Trump administration’s hostility to renewable energy. After losing the tax credits that evened out the playing field with subsidised fossil fuels, there is certainly more headwind. Local opposition to renewables projects also makes future expansion challenging.

As McKibben accepts, two things can be true at the same time: an energy transition led by solar power might be inevitable, and the reduction in emissions might not happen fast enough to avoid the ever more dangerous consequences of global warming. “It’s not going to be easy, but it’s what must happen,” he writes. “We have to bring burning to a halt – or we will burn.”

I agree. Personally, I’d rather bask in the sun.

Topics:

- climate change/

- solar power