Ludovic Slimak helped uncover the remains of Thorin, a Neanderthal

Laure Metz

The Last Neanderthal

Ludovic Slimak (translated by Andrew Brown) (Polity Press (UK, 26 September; US, 24 November))

A Neanderthal skeleton spotted by chance under some leaves, calcified soot and a trove of remarkably tiny arrowheads. These assorted finds from Grotte Mandrin in France have not only transformed our understanding of Neanderthals, but also of the first waves of our species, Homo sapiens, to have reached Europe.

Even more remarkably, the cave has revealed secrets about when the two groups first encountered each other, and why one species subsequently thrived, while the other went extinct. That is the question tackled in The Last Neanderthal: Understanding how humans die, a new book by palaeoanthropologist Ludovic Slimak at the University of Toulouse, France, who led the excavations at Grotte Mandrin.

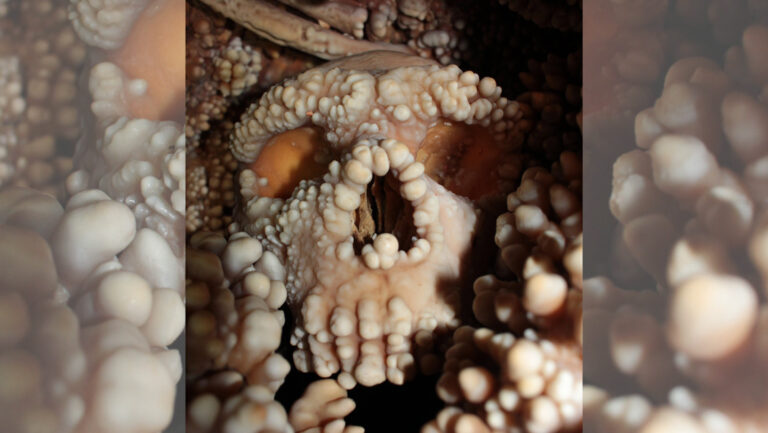

Central to this story is Thorin, a Neanderthal fossil discovered in 2015 just outside the cave entrance, when the sweep of a brush revealed five of his teeth, visible on the soil surface. To preserve every bit of information from this rare find, the bones were painstakingly excavated using tweezers to remove one grain of sand at a time. It took seven years just to recover the remains of his skull and left hand.

The discovery opened up a mystery that took years to solve: different dating techniques produced wildly conflicting results about when Thorin had lived. Eventually, it was confirmed that the fossil was between 42,000 and 50,000 years old, making Thorin one of the last Neanderthals (the species died out entirely around 40,000 years ago). Remarkably, his genome could be sequenced, revealing he was part of a previously unknown lineage that diverged from the main Neanderthal population at least 50,000 years earlier, then existed in extreme isolation.

The Last Neanderthal is a deeply personal and philosophical book that conjures a vivid sense of what it is like to investigate Thorin’s existence and that of the different groups that occupied the cave over millennia. The distinctive smell at Grotte Mandrin, Slimak realises, is from the soot of ancient fires preserved in calcite layers on the walls, forming a black-and-white “bar code”. The bar code can be precisely dated, so bits that have fallen to the floor provide dates for different occupations, revealing that H. sapiens occupied the cave just six months after Neanderthals left. The book conveys Slimak’s astonishment at discovering Thorin hiding in plain sight. “You don’t find a Neanderthal body by taking a stroll through the forest, just like that, lying on the side of the path,” he writes. “It’s crazy.”

The jaw of Thorin, a Neanderthal fossil discovered in 2015

Xavier Muth

Which brings us to the question of why the Neanderthals died out. This is much debated, with the finger typically pointed at extermination by the incoming H. sapiens, or climatic upheaval resulting from a volcanic eruption or a flipping of Earth’s magnetic field. But Slimak has a different view, drawing on evidence found at Grotte Mandrin, in particular a layer of tiny, triangular stone points that were probably used as arrowheads by one of the first waves of H. sapiens to reach the region about 55,000 years ago.

These points are almost identical to artefacts made by H. sapiens in roughly the same time period at a site called Ksar Akil in Lebanon, nearly 4000 kilometres away. This indicates that these people were remarkably efficient at preserving and standardising their traditions across vastly distant social networks, leading Slimak to conclude that they had far more efficient “ways of being in the world” than Neanderthals, who lived in small, isolated groups without such standardisation.

We might like to imagine a dramatic face-off between H. sapiens and Neanderthals, but the reality was totally different, he writes. Drawing on accounts of the collapses of numerous Indigenous groups in Africa, Australia and the Americas after colonisation, Slimak argues that Neanderthal groups slowly fell apart when confronted with others who had a much more efficient way of existing. “It is in the collapse of their views on the reality of the world that humans die… not with a bang but a whimper,” he writes.

“

The bones were painstakingly excavated using tweezers to remove a grain of sand at a time

“

It is a desperately sad eventuality to contemplate, yet immersing yourself in the world of these lost people in The Last Neanderthal is a rare treat.

Topics:

- ancient humans/

- Book review