Geothermal power could be a key part of the UK’s energy mix in the future

Jim West/Alamy

Clearing the Air

Hannah Ritchie, Chatto & Windus (UK); MIT Press (US, out 3 March 2026)

A few weeks ago, I was having dinner with some friends and the conversation meandered – as it will when there is a climate journalist, a campaigner and two civil servants seated at the table – onto the topic of renewable energy.

As you may have already guessed, I was dining with some pretty clued-up individuals, well-versed in the dangers of climate change and the urgent need to switch to cleaner forms of power. But still, the question was posed to me: surely we will still need some gas in our power grids for back-up fuel? A country like the UK can’t rely on just wind, solar and batteries during the dull and dark winter months, can it?

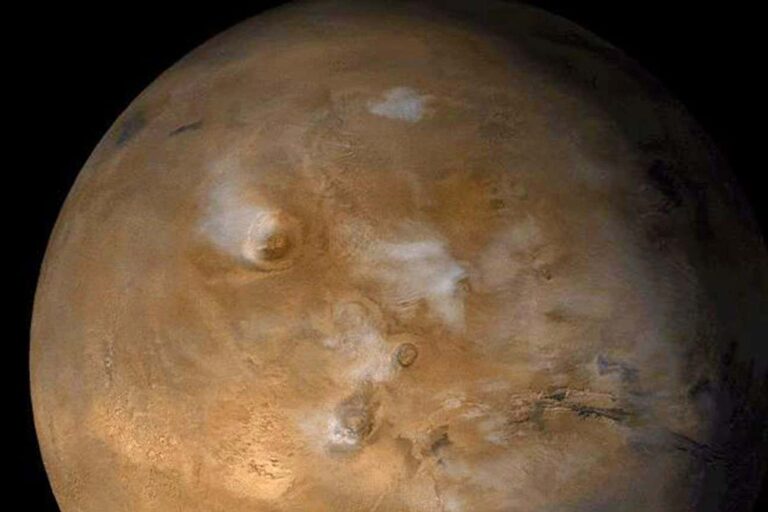

It is moments like these when data scientist Hannah Ritchie’s new book, Clearing the Air: A hopeful guide to solving climate change in 50 questions and answers, excels. Thanks to my well-thumbed copy, I was able to take my friends on a whistle-stop tour of some of the storage options that could help power the grid when the wind doesn’t blow and the sun doesn’t shine. Pumped hydropower, geothermal energy and hydrogen could all play a role, I told them.

Ritchie’s previous book, Not the End of the World, was a crash course in how to solve the planet’s environmental challenges. Clearing the Air strikes the same optimistic tone, but is more of a “how to” guide, providing data-led answers to any questions you may have about the road to net zero.

The queries are organised by topic, ranging from fossil fuels and renewable energy to electric cars and home heating. Reading it, you can’t help but feel this is Ritchie’s response to the ongoing deluge of ill-informed – and often outright misleading – media reports and political pronouncements on the net-zero transition, the kind that tell people electric cars will run out of juice on the motorway, heat pumps don’t work in cold weather and the world doesn’t have enough spare land for solar power.

Clearing the Air pushes back on this disinformation using the power of scientific research and quality data. For example, one of the questions Ritchie answers is about whether wind farms kill birds – a favourite attack line of US president Donald Trump. The answer is yes, wind turbines do kill some birds, but that number is dwarfed by the annual kill rate of cats, buildings, cars and pesticides.

Nevertheless, wind turbines do pose a real threat to some bats, migrating birds and birds of prey. But Ritchie is quick to point out that there are measures we can take to reduce the risk, such as tweaking the location of wind farms, painting turbines black and powering down blades during periods of low wind. This is the kind of nuance that you won’t get from a newspaper headline or a political quip, but it is essential for understanding the benefits and risks of our shift to clean energy.

Each question-and-answer sequence follows the same format, which makes this an easy read to dip in and out of, but it veers towards the formulaic if read in one sitting. Clearing the Air works best as a kind of reference guide, to keep within close reach when a climate-sceptic uncle turns up for Christmas dinner, say.

Throughout, Ritchie’s now-trademark optimism shines through. She makes it clear that for nearly every aspect of the net-zero transition, we have viable options for decarbonisation, without shying away from the challenges or straying into wishful thinking. The effect is powerful: you come away feeling informed and hopeful, with the confidence that it will be possible for humanity to navigate a path out of the climate crisis. In a world of fake news and political spin, this book is a breath of fresh air.

Topics: